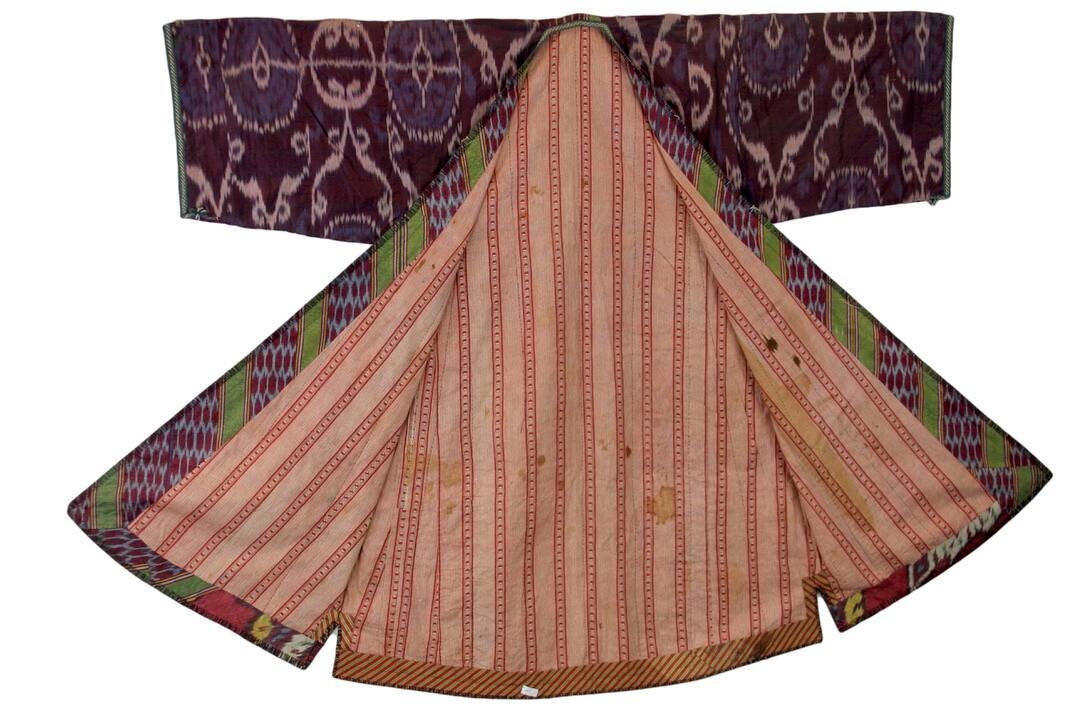

Silk Ikat Coat

Appraiser

Maker/Artist from Central Asia

Date1866-1899

PeriodRussian Empire

Place MadeBukhara, Samarkand and the Fergana Valley, Uzbekistan, Asia

MediumSilk, ikat.

Dimensions146 x 125.7 cm (57 1/2 x 49 1/2 in.)

Credit LineGift of Jeffrey Krauss

Object number2019.1.1

On View

Not on viewLabel TextThis coat’s pinched waist indicates that it belonged to a woman. It is t-shaped with long sleeves and an opening to the front. The length of the coat usually goes to the knee or ankle. The padded coat, filled with cotton, was used in the winter to keep warm. The Ikat coat is lined with a trim in a two-strand warp or embroidery and added hand-stitched onto the coat to give the edges more durability and protection. The inside of the robe is composed of different recycled Ikat textiles or striped fabric so none of the textiles go to waste. The inside of this robe is stained from social gatherings such as parties. The exterior of the coat is plum-colored with white and blueish purple designs. Compared to other Ikat coats, this MAC example is a middle-range luxury item.

Ikat textiles flourished in Central Asia in the nineteenth century where artisans drew from traditions of their nomadic culture. It was an expensive commodity used for trade, gifts, and sometimes in women's dowries. Ikat was a way to show status as a piece of the garment the more a person has the higher their status was. The more expensive textiles had more colors and complex designs because they require more work and skills. By the mid-nineteenth century, Ikats were widely used by Central Asians in their everyday lives. Ikat comes from a shortened word mengikat, which is Malay for “to die” or “to bind”. The word abrbandi means cloud binding in Uzbekistan. The word represents the cloud-like blurred effect created when pre-dyed yarn or silk is woven together in slight misalignment of the dyed threads. In the nineteenth century artisans from the central Asian oasis experimented with designs that were reflected in their daily lives, nature, and shapes traditionally found in decorative objects in the region.

Most of the information about our objects comes from original files, which we are currently reviewing. As such, some of the language may reflect past attitudes and practices that are not acceptable. The Madison Art Collection does not condone the use of offensive or harmful language and does not endorse any of the views reflected in outdated documents. We are committed to an approach that is inclusive and respectful, and we wish to correct language that may be harmful or inaccurate. If you have suggestions, please email us at madisonart@jmu.edu.